Native American Veterans Memorial: Seen through a Sculptor’s Eyes

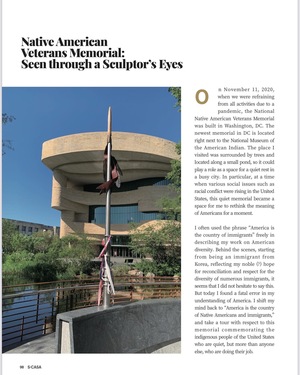

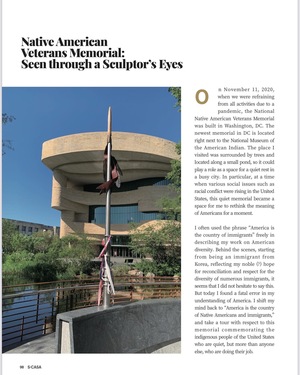

when we were refraining from all activities due to a pandemic, the National Native American Veterans Memorial was built in Washington, DC. The newest memorial in DC is located right next to the National Museum of the American Indian. The place I visited was surrounded by trees and located along a small pond, so it could play a role as a space for a quiet rest in a busy city. In particular, at a time when various social issues such as racial conflict were rising in the United States, this quiet memorial became a space for me to rethink the meaning of Americans for a moment.

I often used the phrase "America is the country of immigrants" freely in describing my work on American diversity. Behind the scenes, starting from being an immigrant from Korea, reflecting my noble (?) hope for reconciliation and respect for the diversity of numerous immigrants, it seems that I did not hesitate to say this. But today I found a fatal error in my understanding of America. I shift my mind back to “America is the country of Native Americans and immigrants,” and take a tour with respect to this memorial commemorating the indigenous people of the United States who are quiet, but more than anyone else, who are doing their job.

The National Native American Veterans Memorial was created with the principle to commemorate Native American veterans, recognize the sacrifices of their families, and create a blessed and healed space for all who visit. The memorial hall was designed by Harvey Pratt, a multimedia artist who won the 2018 international competition. Harvey Pratt is a U.S. Marine, a veteran of the Vietnam War, and a Native American - a member of the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes of Oklahoma. He said that while searching for the location of the memorial hall, a hawk suddenly appeared in the air and stayed for a long time in a tree located in a place that would become the site of the memorial hall. (His great-grandfather's Indian name is “Red Tail Hawk” and he says the appearance of the hawk was the ancestors' appearance to bless this project.)

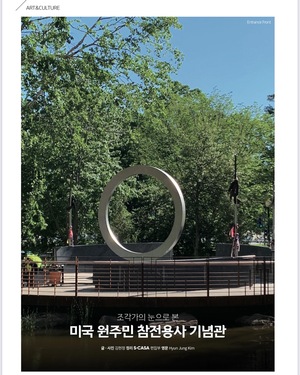

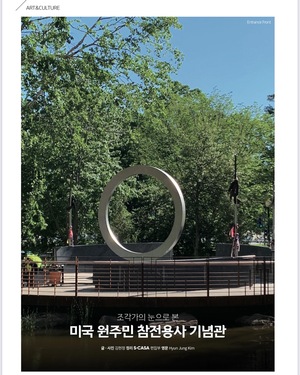

The memorial hall, which can be seen in anecdotes of the location selection, was designed in close connection with the Indigenous beliefs of Native Americans. The memorial is surrounded by trees and water. We walk along a narrow, winding path called "Path of life" from its entrance, and the rusty railings on the side of the water are impressive. Considering the construction of the memorial hall is less than a year old, the appearance of the oxidized railing makes us consider whether it intentionally reflects the natural passage of time. The center of the memorial hall is a 12-foot stainless steel circular structure installed at right angles on a cylindrical stone drum. The circumference is carved with a ripple pattern, and water flows out of the center, circulating throughout the drum. In the inside of the large circular structure, there is fire which can be lit during special events. Regarding this archetype, Pratt says that this shape symbolizes nature such as the moon and the sun, and symbolizes the cycle of life and seasons. In addition, this circular empty space is a passage leading to the sky, and all elements of nature such as water, fire, earth, and air are incorporated into his design.

There is another circular space surrounding this vertical circular structure. There are walls made of stone, and the inside is the form of a bench to sit on, and on the outside, there is a space for walking around the structure. On the four sides of this wall, there are large lancers which are prayer poles, whose ends are cast in the shape of feathers. Each one is decorated with white, red, yellow, and black fabrics. This prayer pole induces the participation of visitors, who write their prayers on a long cloth and hang them on each prayer rod, and the natives believe that these prayer strings are blown through the wind and their wishes are delivered to heaven. In addition, in the forest of trees surrounding the monument structure, recorded songs of various native tribes are played, and the sound, which is like a repeated incantation, makes you feel that you are in a ritual. This space, in which you can experience spiritual moments, is reminiscent of Korean shaman rituals such as Seo-Nang-Dang, Sott-Dae, and Gut, which are very similar in shape and role.

(Seo-Nang-Dang is a shrine tree for village guardian. It is located at the entrance of a town and decorated with five-colored strings which resonate the neighborhood prayers for good luck and good fortune. Sott-Dae is a tall pole decorated with the shape of a bird like a duck as a medium connecting the sky and the world. Gut is a shaman ritual performance including music and dance.)

In addition to this grand traditional interpretation, the memorial hall simply reminds us of our camping in nature, lighting a small bonfire, and sitting around it. In the warmth we share, have we all dissolved our fatigue, become closer to one another, and recovered? Pratt, who claimed that he is a dreamer, says ‘we are all different but all the same.’ Today I became a dreamer with the indigenous people here and dream that each of us, wounded in the small wars of the world, will take a break in this space of healing, understand each other, and blow our wishes into the sky together.

when we were refraining from all activities due to a pandemic, the National Native American Veterans Memorial was built in Washington, DC. The newest memorial in DC is located right next to the National Museum of the American Indian. The place I visited was surrounded by trees and located along a small pond, so it could play a role as a space for a quiet rest in a busy city. In particular, at a time when various social issues such as racial conflict were rising in the United States, this quiet memorial became a space for me to rethink the meaning of Americans for a moment.

I often used the phrase "America is the country of immigrants" freely in describing my work on American diversity. Behind the scenes, starting from being an immigrant from Korea, reflecting my noble (?) hope for reconciliation and respect for the diversity of numerous immigrants, it seems that I did not hesitate to say this. But today I found a fatal error in my understanding of America. I shift my mind back to “America is the country of Native Americans and immigrants,” and take a tour with respect to this memorial commemorating the indigenous people of the United States who are quiet, but more than anyone else, who are doing their job.

The National Native American Veterans Memorial was created with the principle to commemorate Native American veterans, recognize the sacrifices of their families, and create a blessed and healed space for all who visit. The memorial hall was designed by Harvey Pratt, a multimedia artist who won the 2018 international competition. Harvey Pratt is a U.S. Marine, a veteran of the Vietnam War, and a Native American - a member of the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes of Oklahoma. He said that while searching for the location of the memorial hall, a hawk suddenly appeared in the air and stayed for a long time in a tree located in a place that would become the site of the memorial hall. (His great-grandfather's Indian name is “Red Tail Hawk” and he says the appearance of the hawk was the ancestors' appearance to bless this project.)

The memorial hall, which can be seen in anecdotes of the location selection, was designed in close connection with the Indigenous beliefs of Native Americans. The memorial is surrounded by trees and water. We walk along a narrow, winding path called "Path of life" from its entrance, and the rusty railings on the side of the water are impressive. Considering the construction of the memorial hall is less than a year old, the appearance of the oxidized railing makes us consider whether it intentionally reflects the natural passage of time. The center of the memorial hall is a 12-foot stainless steel circular structure installed at right angles on a cylindrical stone drum. The circumference is carved with a ripple pattern, and water flows out of the center, circulating throughout the drum. In the inside of the large circular structure, there is fire which can be lit during special events. Regarding this archetype, Pratt says that this shape symbolizes nature such as the moon and the sun, and symbolizes the cycle of life and seasons. In addition, this circular empty space is a passage leading to the sky, and all elements of nature such as water, fire, earth, and air are incorporated into his design.

There is another circular space surrounding this vertical circular structure. There are walls made of stone, and the inside is the form of a bench to sit on, and on the outside, there is a space for walking around the structure. On the four sides of this wall, there are large lancers which are prayer poles, whose ends are cast in the shape of feathers. Each one is decorated with white, red, yellow, and black fabrics. This prayer pole induces the participation of visitors, who write their prayers on a long cloth and hang them on each prayer rod, and the natives believe that these prayer strings are blown through the wind and their wishes are delivered to heaven. In addition, in the forest of trees surrounding the monument structure, recorded songs of various native tribes are played, and the sound, which is like a repeated incantation, makes you feel that you are in a ritual. This space, in which you can experience spiritual moments, is reminiscent of Korean shaman rituals such as Seo-Nang-Dang, Sott-Dae, and Gut, which are very similar in shape and role.

(Seo-Nang-Dang is a shrine tree for village guardian. It is located at the entrance of a town and decorated with five-colored strings which resonate the neighborhood prayers for good luck and good fortune. Sott-Dae is a tall pole decorated with the shape of a bird like a duck as a medium connecting the sky and the world. Gut is a shaman ritual performance including music and dance.)

In addition to this grand traditional interpretation, the memorial hall simply reminds us of our camping in nature, lighting a small bonfire, and sitting around it. In the warmth we share, have we all dissolved our fatigue, become closer to one another, and recovered? Pratt, who claimed that he is a dreamer, says ‘we are all different but all the same.’ Today I became a dreamer with the indigenous people here and dream that each of us, wounded in the small wars of the world, will take a break in this space of healing, understand each other, and blow our wishes into the sky together.

The Removed Monument Sculptures: Seen through a Sculptor’s Eyes

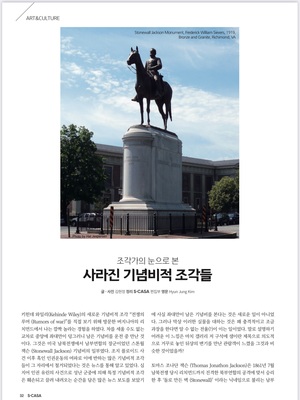

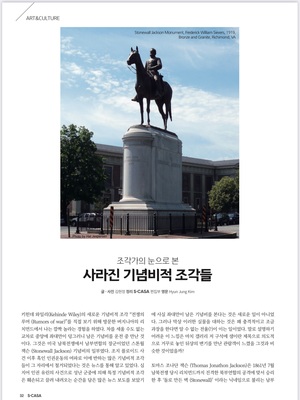

I had a startling experience in Richmond, Virginia on my visit to see Kehinde Wiley's new monumental sculpture "Rumors of War" in person. In the middle of an intersection where cars couldn't be stopped, I saw only its base – all that remains of the monument – while I was driving. It was the part of the monument to Stonewall Jackson, a Confederate general in the American Civil War. As reported by various news agencies, many Confederate-related monuments had been removed after the George Floyd incident as a result of the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement. I had seen numerous news reports of the moment when certain monuments were damaged and/or dragged down by an angry crowd, so it wasn't new to see only the pedestals of monuments remaining. However, it was quite shocking to actually confront these realities when seeing them in person – this feeling, which is difficult to describe in words, seemed similar to what viewers would have felt when they met Duchamp's toilet intentionally placed upside down under the title “Fountain” in the corner of the gallery.

Thomas Jonathon Jackson is a hero of the Confederacy, nicknamed “Stonewall,” after winning the attack by the Union that advanced to Richmond during the Civil War in July 1861. The monument of him riding his horse was cast in bronze and placed on a granite pedestal in 1919, then erected on Monument Avenue, which houses the monuments of other Confederate heroes such as Robert Lee, J. E. B. Stewart, and Jefferson Davis. With the spread of BLM protests in 2020, his sculptures are separated and removed by the city, but only the base that supported the Stonewall Jackson statue remains there.

As a sculptor, I want to pay attention to this left-behind pedestal. In the history of modern sculpture, there has been a shift in thinking that sculptures are no longer placed on the pedestal but come down to the floor, and also the pedestal becomes a sculpture that has meaning in itself. We know Duchamp's work which created the transition of values from an everyday ready-made object to protagonist art by turning the toilet upside down and exhibited in the gallery with the title “Fountain”. The reason why the Stonewall Jackson monument pedestal is reminiscent of Duchamp's Fountain is because this might give some ideas to solve recent debates regarding the demolition of some monumental sculptures.

I don’t think that you will disagree that we should have evaluated our historical figures with the right criteria such as “justice, freedom, human rights, etc.” once again and reposition them in our history. Monument sculptures continues to be a hot topic because it contains the concept of our historical standards of value, and so the demand for change continues. Among these, there are large debates about the issue of the removals of certain monuments - will they be removed or retained as an educational tool as part of our history? After seeing the videos of numerous protesters' violent destruction of monumental sculptures, I couldn't understand them at first and agreed that they should be left as part of a lesson in history. But watching a desperate interview of a black woman changed my mind. She talked about how heartbreaking it is for her and her family to go every day under the monuments of the racists who advocated slavery, taking their position with an example we can easily understand. For them, that monument is like setting up a Nazi symbol in the Jewish community. The moment I heard this story, I felt awakened. I haven't thought about it from the standpoint of those who have suffered. If these monuments should be left as a lesson in history, then whom is the lesson for? Shouldn't the first thing to consider be the group that was hurt and sacrificed? I was ashamed of myself, who couldn’t help to be a third party.

Monumental sculptures containing the wrong past must be removed. Whether it is the matter of formative language (for example, the monumental sculpture of President Lincoln at the D.C. Emancipation Memorial, an equestrian sculpture of President T. Roosevelt in front of the Museum of Natural History in New York, etc.) or the issue of the character him/herself, these memorial sculptures have no value as historical public symbols. Then, can the problem be solved simply by being removal and erasure? I'm still looking for answers to this part, but I think I've found at least two answers in Richmond, Virginia. One of them is to create a new monument sculpture that fits in a new history just like Kehinde Wiley's "Rumors of War". The other is to leave traces of history that have been removed. Stonewall Jackson's remaining pedestal is no longer a secondary role, but has become a monumental sculpture in itself with the traces of history which are the emptied space above and even protestors’ faded marks (almost like the artist's signature on Duchamp's urinal).

The Southern Poverty Law Center, a U.S. non-profit organization that provides legal assistance for victims of human rights issues, has published statistics on racism across the country. Since the death of George Floyd on May 25, 2020, more than 100 public symbols related to human rights violations have been removed. These public symbols are broader than one might think – government buildings, monuments and statues, plaques, schools, parks, counties, cities, military assets, streets, and highways – with monuments and memorial sculptures accounting for the most. On Monument Avenue in Richmond, Virginia where I visited today, 4 figures were removed in 2020 from their pedestals: the figure of J. E. B. Stewart mentioned in the previous article, Stonewall Jackson in the above, Jefferson Davis the former president of the Confederate Army, and Matthew Fontaine Maury, a famous oceanographer and another hero of the Confederacy. Figures disappeared, but the remaining monuments containing the emptied traces become new memorial sculptures. These new memorial sculptures reveal the evaluation of history and stand with even stronger presence as a historical public symbol in each location.

I had a startling experience in Richmond, Virginia on my visit to see Kehinde Wiley's new monumental sculpture "Rumors of War" in person. In the middle of an intersection where cars couldn't be stopped, I saw only its base – all that remains of the monument – while I was driving. It was the part of the monument to Stonewall Jackson, a Confederate general in the American Civil War. As reported by various news agencies, many Confederate-related monuments had been removed after the George Floyd incident as a result of the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement. I had seen numerous news reports of the moment when certain monuments were damaged and/or dragged down by an angry crowd, so it wasn't new to see only the pedestals of monuments remaining. However, it was quite shocking to actually confront these realities when seeing them in person – this feeling, which is difficult to describe in words, seemed similar to what viewers would have felt when they met Duchamp's toilet intentionally placed upside down under the title “Fountain” in the corner of the gallery.

Thomas Jonathon Jackson is a hero of the Confederacy, nicknamed “Stonewall,” after winning the attack by the Union that advanced to Richmond during the Civil War in July 1861. The monument of him riding his horse was cast in bronze and placed on a granite pedestal in 1919, then erected on Monument Avenue, which houses the monuments of other Confederate heroes such as Robert Lee, J. E. B. Stewart, and Jefferson Davis. With the spread of BLM protests in 2020, his sculptures are separated and removed by the city, but only the base that supported the Stonewall Jackson statue remains there.

As a sculptor, I want to pay attention to this left-behind pedestal. In the history of modern sculpture, there has been a shift in thinking that sculptures are no longer placed on the pedestal but come down to the floor, and also the pedestal becomes a sculpture that has meaning in itself. We know Duchamp's work which created the transition of values from an everyday ready-made object to protagonist art by turning the toilet upside down and exhibited in the gallery with the title “Fountain”. The reason why the Stonewall Jackson monument pedestal is reminiscent of Duchamp's Fountain is because this might give some ideas to solve recent debates regarding the demolition of some monumental sculptures.

I don’t think that you will disagree that we should have evaluated our historical figures with the right criteria such as “justice, freedom, human rights, etc.” once again and reposition them in our history. Monument sculptures continues to be a hot topic because it contains the concept of our historical standards of value, and so the demand for change continues. Among these, there are large debates about the issue of the removals of certain monuments - will they be removed or retained as an educational tool as part of our history? After seeing the videos of numerous protesters' violent destruction of monumental sculptures, I couldn't understand them at first and agreed that they should be left as part of a lesson in history. But watching a desperate interview of a black woman changed my mind. She talked about how heartbreaking it is for her and her family to go every day under the monuments of the racists who advocated slavery, taking their position with an example we can easily understand. For them, that monument is like setting up a Nazi symbol in the Jewish community. The moment I heard this story, I felt awakened. I haven't thought about it from the standpoint of those who have suffered. If these monuments should be left as a lesson in history, then whom is the lesson for? Shouldn't the first thing to consider be the group that was hurt and sacrificed? I was ashamed of myself, who couldn’t help to be a third party.

Monumental sculptures containing the wrong past must be removed. Whether it is the matter of formative language (for example, the monumental sculpture of President Lincoln at the D.C. Emancipation Memorial, an equestrian sculpture of President T. Roosevelt in front of the Museum of Natural History in New York, etc.) or the issue of the character him/herself, these memorial sculptures have no value as historical public symbols. Then, can the problem be solved simply by being removal and erasure? I'm still looking for answers to this part, but I think I've found at least two answers in Richmond, Virginia. One of them is to create a new monument sculpture that fits in a new history just like Kehinde Wiley's "Rumors of War". The other is to leave traces of history that have been removed. Stonewall Jackson's remaining pedestal is no longer a secondary role, but has become a monumental sculpture in itself with the traces of history which are the emptied space above and even protestors’ faded marks (almost like the artist's signature on Duchamp's urinal).

The Southern Poverty Law Center, a U.S. non-profit organization that provides legal assistance for victims of human rights issues, has published statistics on racism across the country. Since the death of George Floyd on May 25, 2020, more than 100 public symbols related to human rights violations have been removed. These public symbols are broader than one might think – government buildings, monuments and statues, plaques, schools, parks, counties, cities, military assets, streets, and highways – with monuments and memorial sculptures accounting for the most. On Monument Avenue in Richmond, Virginia where I visited today, 4 figures were removed in 2020 from their pedestals: the figure of J. E. B. Stewart mentioned in the previous article, Stonewall Jackson in the above, Jefferson Davis the former president of the Confederate Army, and Matthew Fontaine Maury, a famous oceanographer and another hero of the Confederacy. Figures disappeared, but the remaining monuments containing the emptied traces become new memorial sculptures. These new memorial sculptures reveal the evaluation of history and stand with even stronger presence as a historical public symbol in each location.

The New Monumental Sculpture “Rumors of Wars”: Seen through a Sculptor’s Eyes

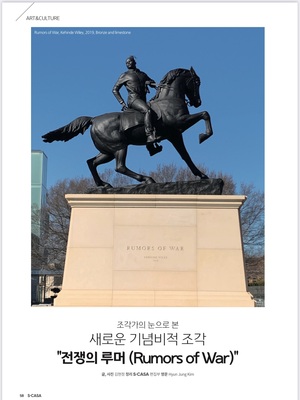

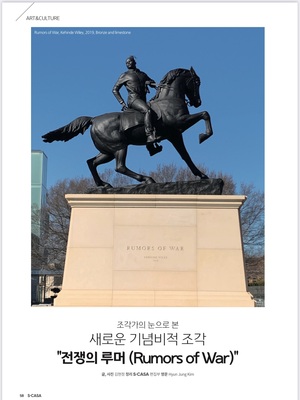

A familiar but unfamiliar monumental sculpture was installed in front of the Virginia Museum of Fine Art. Titled “Rumors of War,” this sculpture was made in 2019 by American Artist, Kehinde Wiley (1977-) and is also known as the largest commissioned work in the history of the Virginia Museum of Fine Art. Kehinde Wiley, who is well known for his portrait of President Barack Obama, is African-American and his work is modeled mainly on young black men like himself. He makes the scenes of traditional art history, especially the poses of portraits of historical figures representing status and authority, imitated by young black men, and then photographs or creates oil paintings of them. These characters are purposely created with colorful and decorative frames and backgrounds reminiscent of classic works from various cultures, and this subtle harmony of traditional styles and modern characters creates his unique visual language.

One of his paintings was also on display at the Virginia Museum of Fine Art, where I visited to see the "Rumors of War". This work was created by replacing the portrait of Willem Van Heythuysen, a cloth merchant from Haarlem, Netherlands, in 1625 with a portrait of a young black man in Harlem, New York in 2006. The character in this work imitates the poses and attitudes of the original portrait as they are and was produced in a larger size than the real one. Unlike the thick gold frame and the background of colorful, decorative floral patterns that are often used in traditional portraits, the person in it wore Sean John streetwear and Timberland boots, which were trendy items in New York in 2006. This possibly awkward and unexpected combination could be found in Wiley's sculpture as well.

The “Rumors of War” sculpture has the appearance of a monumental sculpture that we are quite familiar with. The fact that the figures depicted realistically on the sturdy marble pedestal are cast in bronze is a form of expression of traditional monument sculptures that can be found in many places. Wiley's 27-foot tall 16-foot long sculpture was intentionally used in this style; cast in almost black, dark bronze statue is on top of a familiar trapezoidal stone pedestal. The person rides on a muscular horse and takes a heroic pose as if he were standing at the forefront of the war and heading for the goal. However, the person here is not the kind of war hero we might expect. The figure in this sculpture is like our young black friend we can meet while walking through the streets of Brooklyn or Harlem. The figure on the saddle is my friend who has dreadlocks – representing his heritage, who is wearing jeans torn at the knee – the kind we have in our closet, and high-top Nike sneakers – like many young men want.

Wiley says that the monumental sculptures of the Confederacy he saw in Richmond, where he visited for his exhibition in 2016, motivated this work. During the American Civil War, Richmond, Virginia, was the capital of the Confederacy. There are still the monuments of Confederate heroes who supported slavery on Monument Avenue in Richmond and we can easily imagine how Wiley would have felt while passing these memorials as an African American. Wiley reveals that among the numerous commemorative sculptures, the statue of Confederate Army General James Ewell Brown “J. E. B.” was used as an inspiration for the “Rumors of War” sculpture, and in fact these two sculptures are very similar except for the figures.

Wiley has used the title of this work by quoting the phrase "Rumors of War" in Matthew 24:6 of the Bible, where Jesus describes the time of disaster. I am still trying to figure out the meaning of this title whether he was trying to express the appearance of a new hero who leads in confusion and disaster ahead of the time of judgment, or whether he commemorates the war for the overthrow of the problem of narrow interpretation of race and values, which previous historical monuments have shown.

On September 27, 2019, this sculpture debuted at Times Square in New York, a place where various people from around the world gather, as if to mark the beginning of a new monumental sculpture history. After a few weeks of exhibition, on December 10, 2019, "Rumors of War" was moved to Richmond, Virginia, and permanently installed, where Wiley was inspired, and also has the historical sense for the new monument. I visited Richmond in January 2021 to see this sculpture in person, and ironically there is no longer a statue of James Ewell Brown (J. E. B.), which was an inspiring sculpture for "Rumors of War" production. With the aftereffect of the Black Lives Matter movement following the George Floyd incident, several statues on Monument Avenue were legally removed in July 2020. Then, could I say that the history of monumental sculptures has begun to be rewritten?!

*This article will be continued in “The Removed Monumental Sculptures” in the next issue.

A familiar but unfamiliar monumental sculpture was installed in front of the Virginia Museum of Fine Art. Titled “Rumors of War,” this sculpture was made in 2019 by American Artist, Kehinde Wiley (1977-) and is also known as the largest commissioned work in the history of the Virginia Museum of Fine Art. Kehinde Wiley, who is well known for his portrait of President Barack Obama, is African-American and his work is modeled mainly on young black men like himself. He makes the scenes of traditional art history, especially the poses of portraits of historical figures representing status and authority, imitated by young black men, and then photographs or creates oil paintings of them. These characters are purposely created with colorful and decorative frames and backgrounds reminiscent of classic works from various cultures, and this subtle harmony of traditional styles and modern characters creates his unique visual language.

One of his paintings was also on display at the Virginia Museum of Fine Art, where I visited to see the "Rumors of War". This work was created by replacing the portrait of Willem Van Heythuysen, a cloth merchant from Haarlem, Netherlands, in 1625 with a portrait of a young black man in Harlem, New York in 2006. The character in this work imitates the poses and attitudes of the original portrait as they are and was produced in a larger size than the real one. Unlike the thick gold frame and the background of colorful, decorative floral patterns that are often used in traditional portraits, the person in it wore Sean John streetwear and Timberland boots, which were trendy items in New York in 2006. This possibly awkward and unexpected combination could be found in Wiley's sculpture as well.

The “Rumors of War” sculpture has the appearance of a monumental sculpture that we are quite familiar with. The fact that the figures depicted realistically on the sturdy marble pedestal are cast in bronze is a form of expression of traditional monument sculptures that can be found in many places. Wiley's 27-foot tall 16-foot long sculpture was intentionally used in this style; cast in almost black, dark bronze statue is on top of a familiar trapezoidal stone pedestal. The person rides on a muscular horse and takes a heroic pose as if he were standing at the forefront of the war and heading for the goal. However, the person here is not the kind of war hero we might expect. The figure in this sculpture is like our young black friend we can meet while walking through the streets of Brooklyn or Harlem. The figure on the saddle is my friend who has dreadlocks – representing his heritage, who is wearing jeans torn at the knee – the kind we have in our closet, and high-top Nike sneakers – like many young men want.

Wiley says that the monumental sculptures of the Confederacy he saw in Richmond, where he visited for his exhibition in 2016, motivated this work. During the American Civil War, Richmond, Virginia, was the capital of the Confederacy. There are still the monuments of Confederate heroes who supported slavery on Monument Avenue in Richmond and we can easily imagine how Wiley would have felt while passing these memorials as an African American. Wiley reveals that among the numerous commemorative sculptures, the statue of Confederate Army General James Ewell Brown “J. E. B.” was used as an inspiration for the “Rumors of War” sculpture, and in fact these two sculptures are very similar except for the figures.

Wiley has used the title of this work by quoting the phrase "Rumors of War" in Matthew 24:6 of the Bible, where Jesus describes the time of disaster. I am still trying to figure out the meaning of this title whether he was trying to express the appearance of a new hero who leads in confusion and disaster ahead of the time of judgment, or whether he commemorates the war for the overthrow of the problem of narrow interpretation of race and values, which previous historical monuments have shown.

On September 27, 2019, this sculpture debuted at Times Square in New York, a place where various people from around the world gather, as if to mark the beginning of a new monumental sculpture history. After a few weeks of exhibition, on December 10, 2019, "Rumors of War" was moved to Richmond, Virginia, and permanently installed, where Wiley was inspired, and also has the historical sense for the new monument. I visited Richmond in January 2021 to see this sculpture in person, and ironically there is no longer a statue of James Ewell Brown (J. E. B.), which was an inspiring sculpture for "Rumors of War" production. With the aftereffect of the Black Lives Matter movement following the George Floyd incident, several statues on Monument Avenue were legally removed in July 2020. Then, could I say that the history of monumental sculptures has begun to be rewritten?!

*This article will be continued in “The Removed Monumental Sculptures” in the next issue.